It is perhaps not surprising that a particular address was occupied by a succession of photographers. since the rather specialised requirement at least in the early days was for somewhere with plenty of space, but primarily good light. This tended to put these premises towards the top of buildings in the city. John Urie in his memoirs says he was 'obliged to cover three blocks with glass houses' in order to satisfy demand.

For example, the premises occupied by Andrew Bowman from 1867 till 1884 are shown

high in the left hand picture below (Jamaica St. looking NNW), and those of James Bowman high in the right

one (also Jamaica St., looking NNE). In this latter case,

the words 'R. T. Dodd, successor to' can just be seen above the Bowman name, which dates the

picture to after 1887.

Other studios are seen in the pictures below. The first is looking east through St. Vincent Place, and the 'glasshouse' studios of A. & G. Taylor can be seen five flights up on top of the facing building. This picture is dated to 1897, the last year that Taylor is recorded at this address, and the notice on the building states that the block is for sale. The second picture shows the same studio, this time with the legend 'Crawford Hamilton's Studios' which dates the picture to between 1903 and 1908.

The third picture, looking north across Jamaica bridge shows the premises of John Urie, at 83 Jamaica street, where he was from 1869 till 1887

Image above Copyright the Francis Frith Collection

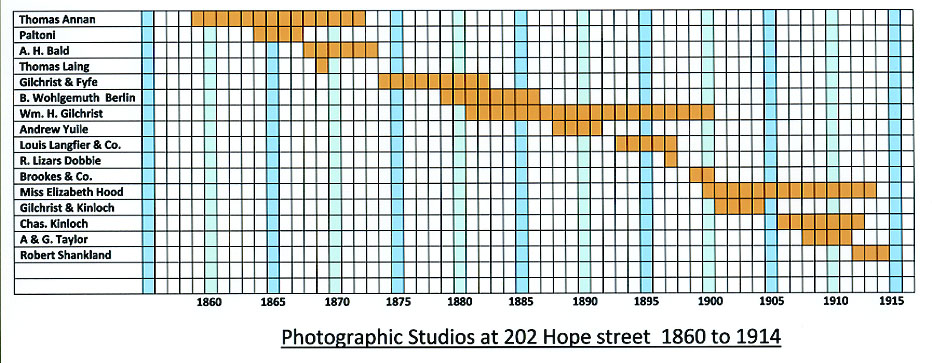

The prime example of a long lived studio, however, is 202 Hope Street, which had at least sixteen different photographer tenants between 1861 and 1914. It was of course a 'high rise' building of its day and in 1899 had 10 tenants of various occupations together at the one time.

Other studios which saw a long series of workers were 184 Paisley road (12 tenants ) 190 Trongate (10 tenants from 1855 till 1883), 85 Buchanan Street, (9 tenants 1854 to 1900), 136 Buchanan Street (10 tenants, 1867 to 1902), 249 Argyle Street (8 tenants from 1857 to 1887), and 46 Jamaica Street (8 tenants 1857 to 1896).

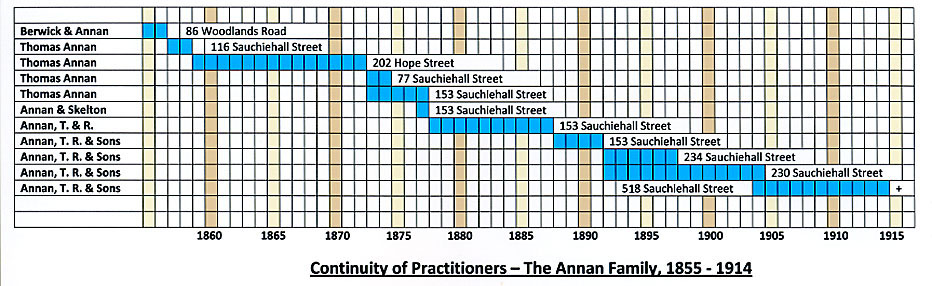

It is also possible to track the movements and development of particular photographers, as they

expanded, moved, and extended their business. The prime example here is Thomas Annan, who

published the famous portfolio of photos of the closes and streets of Glasgow. His business first

included his brother Robert, and then his sons John and James Craig Annan. Other notable

families were the the Douglas's, Ralstons, Stewarts, and Turnbulls.

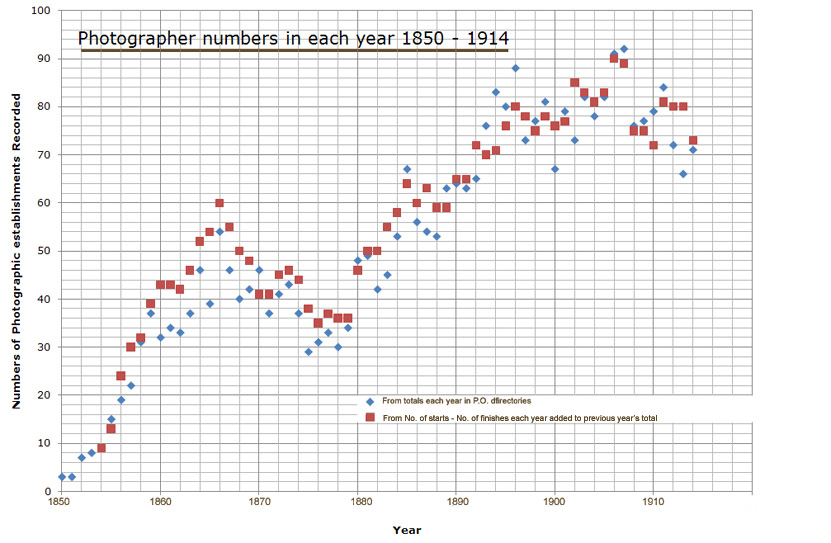

The graph below shows the total number of photographers listed each year from 1854 till 1902. This table is based on the trade directory entries only.

It is easy to understand the rapid rise of numbers from 1855 till 1865, as the new technology became known, and the fashion for stereo cards and then the cartes de visite swept the country. The fall in numbers from 1866 to 1879 is less easy to explain – perhaps the market was oversupplied after the surge in the sixties, and there was a weeding out of the less efficient. From the beginning of the eighties there was then a steady climb in numbers, as the process became cheaper, and started to become available to the amateur. It has to be remembered however that even in 1870 the cost of 12 CdVs was about 7/6d when a clerk’s wages were only about £5.00 a week, and a labourer about half that, so that these items were still a significant expense for all but the rich.

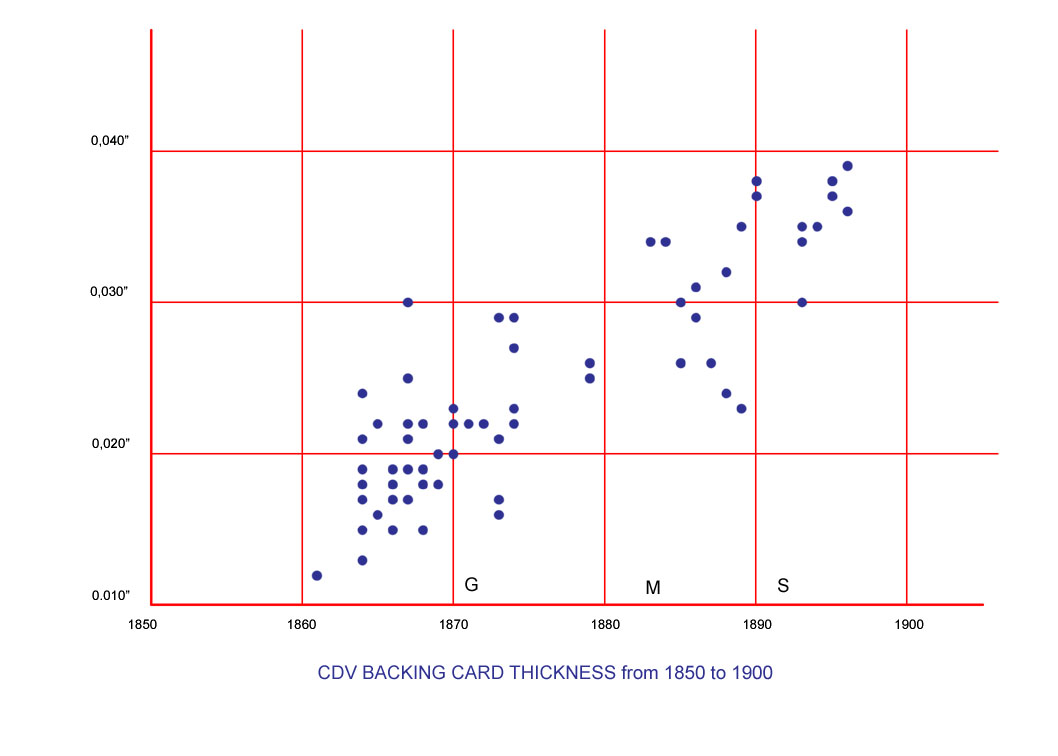

Initially the backing cards were square cornered, but by the 1870s most corners were rounded. Later, in the eighties and nineties there was an occasional return to the square corner. The thickness of the cdv backing card increased over time from the about fifteen thousandths of an inch in the early 1860s to 35 or 40 thousandths by 1900. An attempted is made in the graph below to try and see exactly when that happened, and how. The information has come from cards which can be confidently dated to within a year or so. Obviously not everyone changed cards at the same time; however by the time backing cards were coming from specialist suppliers, and many thousands, if not millions were being used each year, it is likely that changes were widespread and to some extent, coordinated.

While there is an obvious trend with time, the variation is such that only rough indications are possible. We can say that any card thinner than 0.020" is likely to be before 1870, and one thicker than 0.030" is likely to be after 1880

Some later cards had gilded or silvered edges, and the edges were chamfered ('mitred') as well. Provisional dates for these innovations are marked in the graph above by the letters 'G', 'S' and 'M' respectively, though it has to be stressed that these dates are based on a relatively small collection, and could well be earlier.